The two mothers-in-law could also mime their mutually feelings in the broygez tants.("dance of anger") and in the sholem tants.("("dance of peace").

Jewish dancers by Mysrael

Yiddish, Klezmer, Ashkenazic or 'shtetl' dances

Ashkenazic Jews have played and danced to klezmer since the 16th century, primarily during the period of a traditional wedding. But at no period did they perform exclusively dances that were peculiar to their communities. Much of the dance repertoire, which might combine line and couple formations, was of a cosmopolitan nature, plus elements from their immediate Gentile neighbors. Nevertheless the Jews practiced a corporeal expressive language that was highly differentiated from that of the non-Jewish peoples of their neighborhood, mainly through motions of the hands and arms, with more intricate legwork by the younger men. Many of the Ashkenazic dance gestures were ultimately speech-related and there seems little doubt that ethical issues came also into play.

| An

essential part of the wedding feast was the ritual, in which honored

guests, the fathers-in law, elder relatives, rabbis, etc. danced to

slow elaborate tunes, for example for the bride (mitzve

tants). The two mothers-in-law could also mime their mutually feelings in the broygez tants.("dance of anger") and in the sholem tants.("("dance of peace"). |

Dancing Jews by

Zofia Stryjenska (1929)

|

Jewish dancers by Mysrael |

In many 'misnagdic' (non-Hasidic) communities, the freylekhs the sher the Polish patsh tants etc. might be danced by mixed couples. In the more observant ones, Jewish male dancers used to dance separated from women.

Since the Renaissance, the European aristocracies and peasantry more and more favored couple dance (in which the partners of opposite sexes held one another by the hand or waist) and contra dances (with changing of partners). As minimum requirement of ethical decorum, the Jews introduced the use of a 'tikhele' (handkerchief) as a mean of separating the sexes where they did dance together (Zev Feldman).

The solo dance category had both a folkloric as well as a professional aspect. Good male dancers often preferred to dance as soloists -indeed they might pay the klezmorim just for this privilege- but this might also be performed by a professional dancer attached to the kapelye (klezmer band), or by a dancing badkhn (master of ceremony).

Solo dancing might also have a comical or even a grotesque, parodic aspect, depending on the character of the dancer and the mood of the occasion.

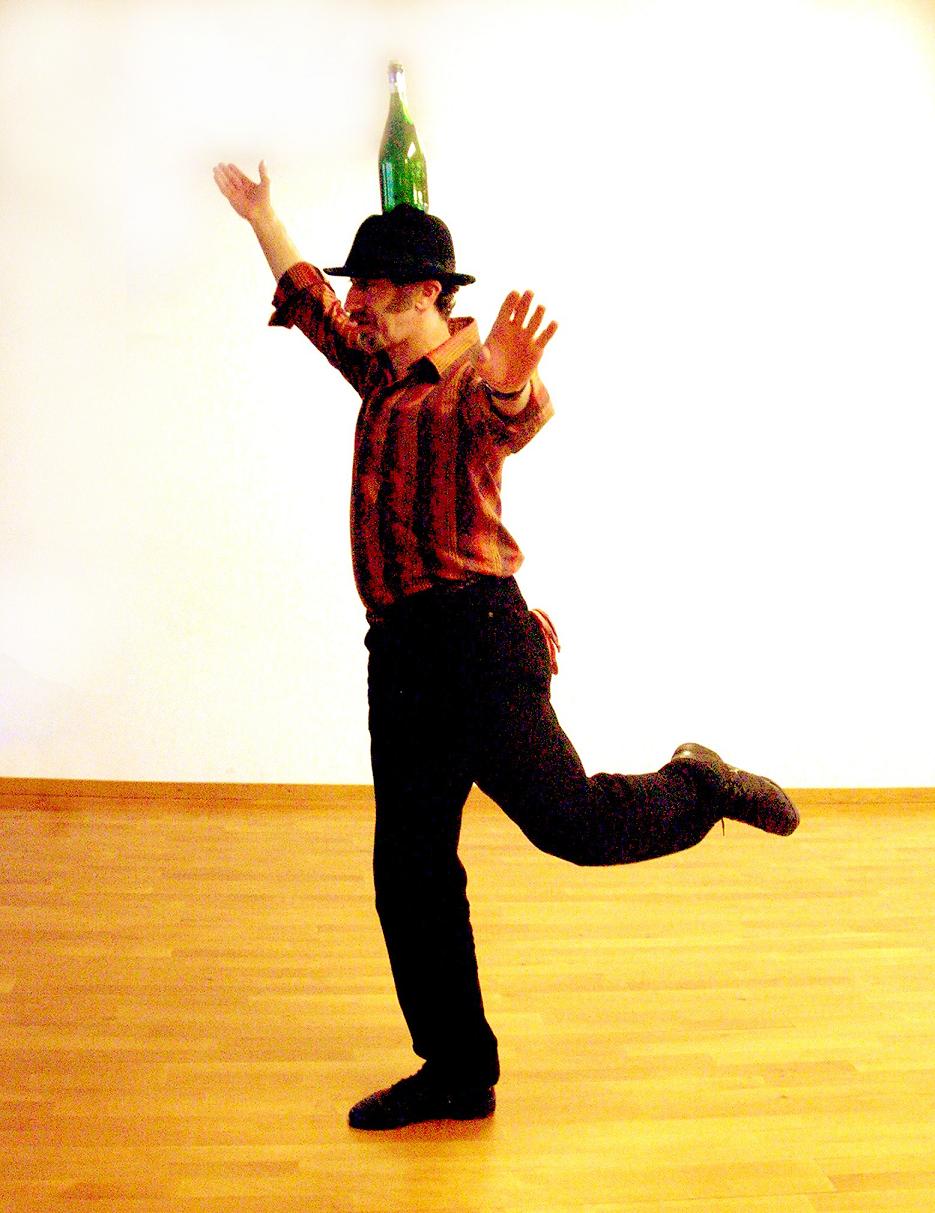

| One type of solo display

dance involved balancing a bottle on the dancer’s head (flash tants).

Or a dancer might also dance bare-foot on a mirror to display his agility ! |

|

Steve Weintraub performing the 'flash tants'

|

Since the first quarter of the 19th century, Hasidim ritualized and sacralized many aspects of Jewish life that had previously been subject to secular fashions, including in the realm of dance. They adopted older traditional Ashkenazic wedding dances and strengthened patriarchal and mystical elements at the expense of the erotic and ludic elements that were common among non-Hasidic communities. They also blended the older communal functions with ecstatic religious devotion, emphasizing movements of the arms and hands as well as the legs (Zev Feldman).

|

Mekhutonim tants (in-laws dance) Galicia, late 19th century (anonymous artist) |

The choreographic system that emerged seems to have been fairly stable over most of the area of Jewish settlement in Eastern Europe from earlier to mid-19th century only until the end of the 20th century. By then modernization and Enlightenment, and in some places (parts of Hungary, Moldavia and Wallachia) cultural assimilation, weakened the practice of the system. The First World War and the Russian Revolution marked the end of this choreographic system as the dominant one. After the Holocaust traditional Ashkenazic dance was still practiced among some Yiddish-speaking communities in the former Soviet Union and among members of the landsmanshaftn culture in the United States, especially in New York and Philadelphia.

![]()

The sher was the center of general

Ashkenazic dancing. The name received

various folk etymologies. The sher emphasizes the typical Ashkenazic

body posture and hand

gestures and furnishes an opportunity for the women to employ shoulders

and arms to create

a subtly flirtatious mood.

The participants number four mixed couples (in more pious

communities four female

couples). An initial circle formation breaks into a couples promenade,

after which the

first male dancer invites his partner to circle with him in the center.

This process is

repeated by all the dancers in turn, and each dancer also has a turn at

a brief solo dance

in the center. At the close of each cycle the circle formation is

repeated. The music of

the sher is usually of the same character as freylekhs, except that

many tunes in

succession must be used for the length of the dance (Zev Feldman).

The sher was universally regarded as a "Jewish" dance both by the Jews

and the

Gentile. It was diffused from the Baltic to the Black Seas and borrowed

by Moldavians and

Ukrainians. In America it was preserved both among the landsmanshaften

(communities from one shtetl)

and among the leftists (who

appreciated it secular nature) into the 1960s and beyond.

The khosidl has a Hasidic character, although it was not a Hasidic dance. It is as a semi-sacred solo or collective dance, based on a zemerl (melody with religious inspiration). It usually begins at a moderate tempo, but quickens little by little until reaching an ecstatic religious enthusiasm.

The mimetic aspect of Jewish dance was most pronounced in the broygez tants ("dance of anger"), a wedding dance in which the mothers-in-law expressed their mistrustful relationship. Generally one woman acts offended while the other attempts to mollify her. The scene ends with a sholem tants in which they become reconciled. The broygez tants can also be danced by a man and a woman outside of the wedding context.

The hora is a slow, circle (ou line) dance in a triple meter. It was common to the Jews and the goyim in Romania (Moldavia, Bessarabia, Bukovina) and in some regions of Ukraine. The steps are slow and bearlike, allowing young and old people to dance it together, and giving to the dance a spiritual stamp.

The freylekh is the most common, basic and widespread East-European line or circle dance, often practiced at weddings, Bar-Mitzves and other 'simkhes'. It's characterized by a shuffling walk and a two-step, alternately stepping and stomping. The leader can promote some spectacular or funny figures, like the 'snake' (oyfvikln zikh), the 'Grand March', 'Threading the needle' (nodl un fodn), or start a improvised part with solo dancings (shaynen).

The bulgar,

also a

brisk circle or line dance, appeared among Romanian and south Ukrainian

Jews at the end of

the 19th century and was exported to the USA

where it beacame extremely

popular.

Being held by the hands, the dancers step

towards the

center or towards back, but increasingly more marked to the right, so

that the

circle turns. The steps are repeated by groups of six and thus shift

compared

to the music, structured over 8 times, which gives to this simple dance

a

complex character with tensions and strong beats.

The terkisher, a line Hassidic dance on a typical 'terkish' (similar to tango or syrtos) rhythm, was widespread in the New World, more than in Eastern Europe.

The sirba is a Romanian dance 'à la serbe', a couple or line dance on a rather up tempo.

The patsh tants is a Polish contra danse in circle. The music is very specific, as it requires, at times, to clap the hands ('patsh mit di handelekh') or to stomp ('tupn mit di fiselekh').

A few remarks about the gesture in yiddish dances:

At the beginning of a dance set, the tempo is usually slow and the movements quiet. They become gradually brisker and more animated. But the women's movements keep always less exuberant than the men!

"Sheynen" (shine) on a sher or on a freylekh is the way for a proster yid (poor or humble Jew) to show his pride: he stalks proudly with thumbs under his braces or in his belt, or a hand behind one ear, etc.

Yiddish dances contain rather few erotic expression! At the very most, a woman can put his feet forward and balance his shoulders on the same side, but you'll never see rapid hip movements as in Arabic dances!

Arms movements delimit a private space where other dancers can be invited or excluded. Many other feelings can be expressed by arms and head movements: anger, contempt, disregard, inquiry, reconciliation, forgiveness, attachment, supplication, etc.

![]()

After the teaching and several texts form Zev Feldman and Michael Alpert.

Un a sheynem dank (a huge thank you) to Helen Winkler for her availability, her enthousiasm and her excellent information ! http://www.angelfire.com/ns/helenwinkler/assorted.html winklerh@hotmail.com

I also want to thank Danielle Bailly who involved me in the writing of her book "La danse traditionnelle juive ashkénaze - signification culturelle", to be published in 2014 by l'Harmattan, Paris.

Please

check also the pages of two famous yiddish dance teachers :

Leon Blank: www.klezmer.se

and Steve Weintraub:

http://profile.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=user.viewprofile&friendid=30423355

![]()

![]() 2007-12-21

2007-12-21

![]()